John Vinton Studio Tour

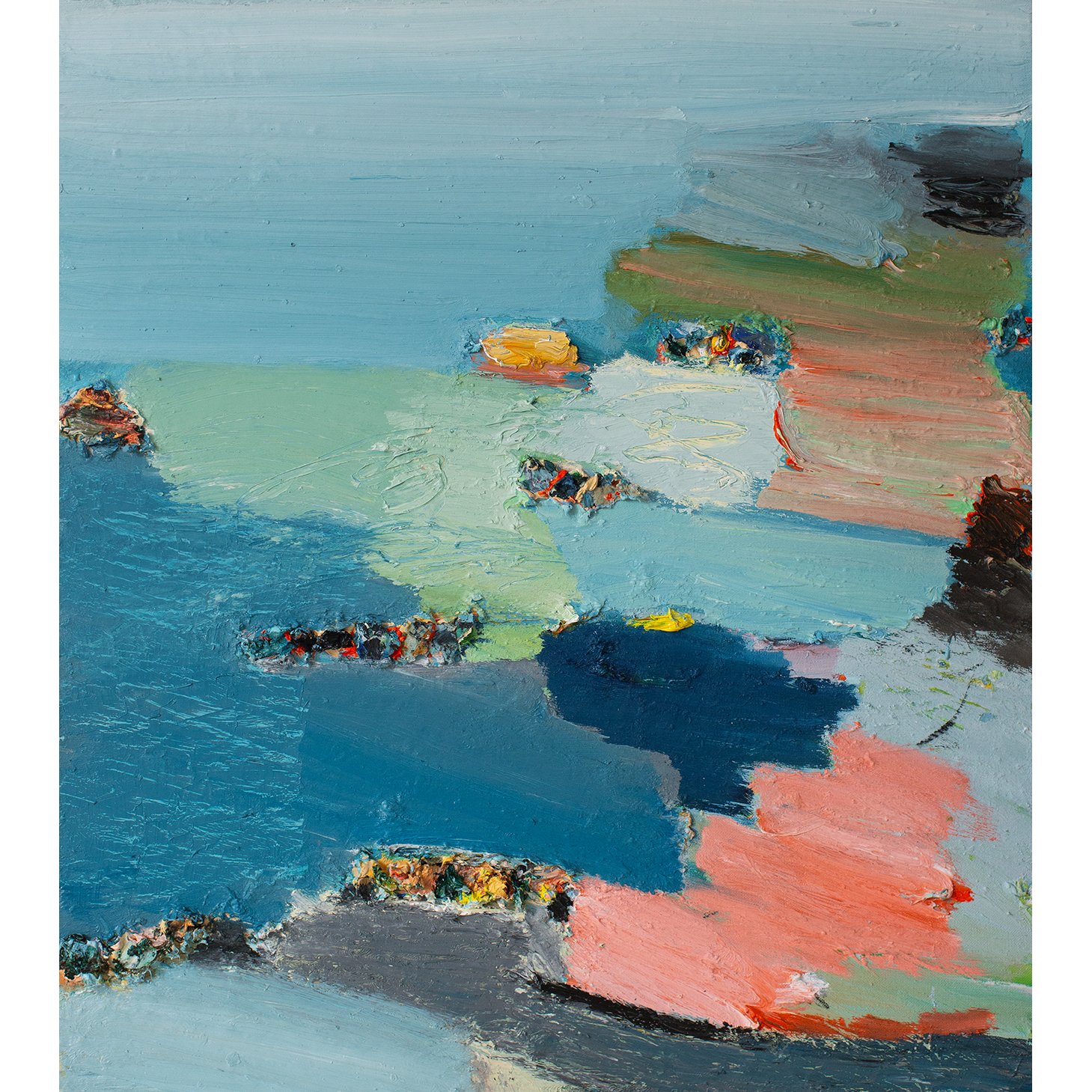

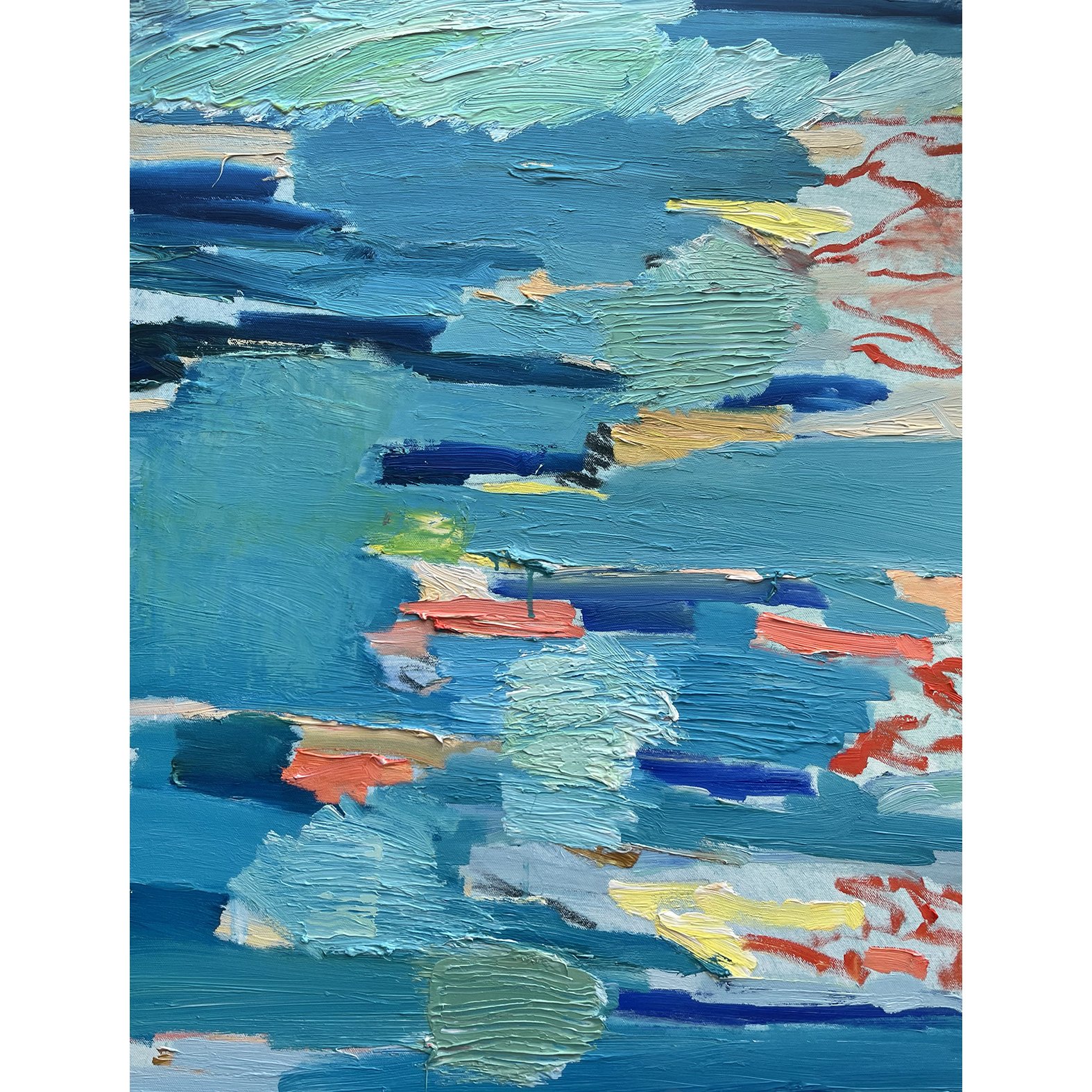

I had the delightful opportunity to visit gallery artist, John Vinton, in his Waltham studio earlier this month. It was a wonderful way to spend a winter afternoon in March - John and I took photographs of him painting in his studio, he showed me work of his from the last few years, and afterwards we had lunch together. It’s always a treat to see any work of art - finished or in-process - up close, but the atmospheric hues and deep layers of John’s work shine in person.

Alongside the photos below is a Q&A with John about his process, his inspiration, his background in architecture, and more. Having just spent an afternoon with John in person, I can perfectly hear his voice in my head, answering the questions below - describing in rich detail how he’s captivated by the way in which water meets land or all of the varied colors and textures he experienced during a trip to the south of France.

Read on for more from John and see glimpses of him at work in his studio space.

What currently inspires your art?

In the last ten years especially I have been focused on doing work that speaks to the places that I love. I can remember being up on a bluff and looking across an expanse of marsh and beach and ocean beyond and thinking how can I stay engaged with this place. You can only look at it for so long then when you look away its gone. Your attention flags, you can’t stay there on and on and be a part of it as you may like. Painting for me is a way to do that, to stay focused, to stick with it and stay engaged. Using size and shape, color, pattern, gesture and composition, especially process happenings that represent a spontaneous capture of the feel of it. A granular textural sweeping visuality that has a feeling of recognition. Yes this is what it feels like. Yes.

How does your background as an architect inform your approach to painting?

Architecture, it seems to me, is the structuring of need and function according to what building technology can provide and what our collective imagination has offered as a way to do things. It’s a way to order our physical lives serving our many personal and societal functions in an invented structure — a cultural expression joining the practical and the creative. The Houses of Parliament. The Taj Mahal. The boulevards of Paris. The streets and light of New York City.

I particularly enjoyed working with the team of professionals required for this effort. A very diverse team with lots of points of view. From designers, engineers, and contractors, to social scientists, programmers, financial experts, cost consultants, public agencies, and not the least, the owners’ team determining limits, vision, and specific requirements. A lot to understand and coordinate, a lot to pull together in support of the goal of designing and constructing just the right project.

One thing learned from all this is that a building is in essence an invention. In order to serve its creation, you have to understand the invention — you need to internalize the essence of it so that you can serve its realization at each step in the complex process of creating it. Coordinating with all the parties in all their disparate characters. Resolving conflicting needs and goals. Offering a persuasive narrative for all parties to work effectively together. All while keeping the undertaking on a positive footing. It’s the understanding you have of the invention that counts. A largely non verbal understanding that needs to be translated and expressed at each point. If you can hold this in mind, you can keep the process on track.

Painting, it strikes me, rests on a similar kind of non-verbal essence. At each step, you are trying to feel what is needed, what the painting needs, and avoid a mental willfulness that can stifle the life that is beginning to emerge. It’s a delicate process that requires using a very non-rational part of ourselves and when we find ourselves too heavily planning next moves, then we need to be careful to keep, as we say, things fresh and spontaneous — giving the painting a chance to stay on track.

In this way, I believe my experience of architecture has informed my practice of painting.

How would you describe your work to a first time viewer?

I’m essentially a landscape painter using abstraction as a prime force in my work. I love the water especially as it meets the land. The huge sweeps as it meets the sky. The granular quality as the wind selectively scurries the surface. The translucent luminescence of sand bar shallows and rocky shelves at the waters edge. The suggestion of rich undersea life that can be seen in various ways from the surface of the water.

All of this can be understood abstractly as well as figuratively. I’m not sure exactly how, but I’m inclined to think that as much as our eyes see according to our rational framework of things and places with names and attributes, they also see and respond to the limitless untitled masses of visuality that we inhabit of a vast range of colors and textures and compositions that are recognized and stored in our memory somewhere and have the real and tangible emotional content that abstraction can elicit. A powerful base that I hope my work will stimulate and engage.

What response do you hope your art might inspire in a first time viewer?

I’m hoping that the work elicits an emotional response in the viewer a feeling of recognition and connection tapping into that wealth of visual experience we all have, a kind of knowledge, a kind of centering that helps us be who we are. We are all such visual creatures. Our eyes are so vitally connected with our brains involving every part of ourselves and what we do. This is a major way we relate to the world and understand it. I’m hoping that my work helps in some small way empower that connection.

How do you know when a work is finished?

While you are working on them, paintings are open and accessible going up and down as you work your way through the process of seeing weighing editing revising starting over discovering all in the search for something fresh and meaningful and active. This can go on for weeks in some cases. Then the painting closes. It becomes as if it were done by someone else. It’s no longer open and accessible. To work further is possible but would change things that had become settled being in essence a new start on an old surface. Certainly possible and sometimes desirable but only at a cost. For the most part, I try to catch the work when it begins to close, while still fresh and open, with lots to say and stop. That’s when I feel it’s finished.

What does your process look like?

I tend to work on multiple pieces at the same time. My ideal situation is to have my studio walls lined with fresh canvases which I can approach moving from one to the other as the process dictates. Then as one becomes more dominant, I may work mostly on that piece for a while. I often reach a point where a canvas has something working and I’m not sure what the next step is. One approach that I often use is to then put a blank canvas next to it and work to bring this new one along related to the piece I’m setting aside for the moment. When I then have the new piece there, I can decide which to proceed with next — either the new one, which has been brought to a level whereby I can now resume work on the old one in light of what I’ve learned in the new one, or vice versa. I’m also keeping an eye on the work, always trying to keep it fresh and allow it to be what it wants to be.

Some work starts with sketches on-site — either small 4x6in watercolors or small acrylic 16x20in or 20x24in paintings which dry fast and allow for rapid applications of layers. I also take lots of photos with my phone which I refer to from time to time — not so much to reproduce the scene, but rather to jog my memory of how it felt.

Which artists inspire you the most?

So many, but I started with Winslow Homer and his incredible watercolors of the Caribbean of sailors, boats, skies, fishermen, and the captivating hues of the ever-shifting water. Then in my time at MOMA as a young man, all the early 20th century greats — especially Matisse and his paintings of Morocco. While painting in Brockton in the late 1960s, some of the work I saw in person made an impact: the early Ocean Park paintings by Richard Diebenkhorn, a Cy Twombly blackboard painting at the Yale Gallery of Art, and reproductions of a series of small sketches John Frederick Kensett made one summer in the late 1800s on islands off the coast of Connecticut. Later on, a show of Eduard Manet’s small exquisite paintings of flowers and platters of scallops and other tiny sea creatures which were completed, like Kensett’s sketches, during the last few years of his life.

There are so many great artists! Joan Mitchell, Willem de Kooning’s landscapes, John Walker’s studies of Maine waters, but I must say I keep going back these: Winslow Homer, Henri Matisse, Richard Diebenkhorn, Cy Twombly, John Frederick Kensett, and Eduard Manet.

What drives you to create?

As someone once said to me, if you’re an artist, you’ll just create whether you want to or not. Even though that’s kind of a “Romantic” poet’s view of artists, it has some validity.

I started as a school boy in a Saturday class my older sister and her friends all liked and found that I liked it too. Mr. Nokes’s dictum was that anyone can draw and paint — if you just get right to it, you’ll be surprised how much you can do. And he was right, instilling a healthy can do sense of accomplishment in us fledgling artists. Earlier, my mother had given me an activity book from the Metropoliitan Museum of Art that had stickers and a coloring book ordinary enough except the images were by Winslow Homer after his watercolors of the Caribbean, incredibly compelling. I can still see them in my mind’s eye. This was my start.

After graduating from college, I found I couldn’t quite make the leap to graduate school yet. I needed a break, so I stepped back and remembering Mr. Nokes, decided to learn to paint, bringing on a flurry of studio work during the five years between college and graduate school. Then acceding, I thought, to the practical realities of life, I put down my paints and studied to become an architect, thinking that this would satisfy the urge to make things but as it happened it never seemed to. Architecture became my 9 to 5 day job, yes, with lots of satisfaction, but I always found myself pulling away for a little timeout with paints and brushes.

I never saw this either as a pastime, a hobby, or just a way to relax, but rather something more essential for me. I kept thinking back to my first studio in the old repurposed shoe factory making large canvases out of 1x3’s and whatever fabric I could get a hold of, putting to use the new acrylic paints I had purchased from Utrecht Linens in NYC. This was the 1970’s and acrylic paints were the new thing. I had seen a TV show about the Yale School of Art and imagined myself in one of those student cubicles making paintings of a certain size. One of the AbEx painters I admired said he liked paintings that are his size or larger so that there could be an even give and take. I loved Helen Frankenthaler’s even more and hers were even larger.

I focused on painting for five years having various part time jobs including delivering donuts while working away in my studio during the day. Toward the end of this period I even had work accepted by the fledgling Boston ICA Lending Gallery and just as I was starting architecture school at Harvard, the ICA both sold a painting and placed my work in a show at Thayer Academy called Eight Boston Abstractionists. I was both delighted and taken aback but nonetheless continued with the plan to study architecture. This was spring 1971.

And though I persisted, I never lost the urge to paint and eventually came back to it. During the last several decades of my architecture career I managed to have a dual life both practicing architecture — my last major project was a new classroom building for a university in the Boston area, — and developing paintings in my SoWa studio in the SoWa Arts. I enrolled at Mass Art and then the Post Baccalaureate Studio Arts Program at Brandeis in order to touch up my skills. It gave me access to a whole new network of Boston area arts figures and organizations.

So why do I paint? I’m not sure that I see any alternative. Painting gives me a way to understand my life and the forces and places that are important to me. It gives me a way to work with all this and put some of it down to share with others. To me, this seems like a pretty good way to go.

Your favorite museums?

In my early 20s, I discovered MOMA and made frequent pilgrimages to NYC on the bus, learning about art in the 20th century. This was the original MOMA of the 1960’s in which the western canon of modernist art and design was arranged in a certain order — part chronological and part topical whereby one could walk through the galleries sequentially and see the work of western artists all at once and all together. A powerful and formative experience. With a nod to my earlier MFA and Metropolitan trained sense of art with a room at the end with Monet’s massive pond lily paintings, both relating back to traditional 19th century art and strongly prefiguring the Abstract Expressionist movement yet to come.

The Louvre, of course, is absolutely amazing and totally overwhelming. During my five years of painting between college and graduate school, I practically lived at the Rose Art Museum and The DeCordova, then The Fuller Museum in Brockton once it opened, since my studio was in an old Brockton shoe factory.

Lately I have really been taken by two smaller museums. The Clark in Williamstown where, in an hour, you can see incredible work from Renaissance masters to work by leading contemporary painters, including a large group of Winslow Homer works. I also really enjoy The Frick in NYC, which also is small and has a select group of exquisite paintings beautifully situated and well-lit, offering informative side by side comparisons and a quiet, supportive experience.

A dream travel destination to paint?

My current painting practice is all about place. The places I love and am drawn to. I feel our connection as creatures to the places we inhabit is primary and fundamental to our sense of ourselves. Whether it’s urban or country, city streets or the countryside, mountains, plains, or vistas of water. Our sense of identity is all about these places. So, travel to me is the opportunity to immerse myself in these environments. For me, the last several years it’s been the water and where it meets the land.

The following New England landscapes have all been the focus of my work over the last 15 - 20 years:

Block Island, Corn Neck Road, Truro, The Pamet River, Bay Village Beach, Pilgrim Heights, Wellfleet Harbor, Brewster Flats, the Charles River Basin, Coolidge Point in Manchester MA, and Prouts Neck’s ocean walk and Eastern Point in Maine.

So, these are my dream travel destinations. All nearby and well loved.

Then there are others, too, which will come up as we go along. A few years ago we spent time in southern France. I was struck by a seaside town near Marseille called Cassis. We found an incredible scene there on the town’s nearby Calanque de Port Pin — rugged yellow limestone cliffs, dotted with pines of a light green that just glowed in the sun and all engulfed by the unbelievably intense green-blue Mediterranean water. This was a wow moment for me. I find that this is beginning to creep into my work and warrants another visit. Also a few years back, we spent the month of April on a vineyard in Napa and had the incredible experience of watching the vines come alive. There were just a few tendrils of green when we arrived and four weeks later they were just a riot of green furiously growing — the most amazing demonstration of how fertile this valley is. You almost feel if you were to just stand still in place long enough, that you will start growing too.

How do you spend your time outside of the studio?

With our family and friends, maintaining connections, visiting places of interest, finding time for our favorite museums, and perhaps the symphony — I once worked for a short while on a performance hall in St. Paul, Minnesota, long enough to learn how intricate and sought after great orchestral hall sound is -- Boston’s Symphony hall being amongst the best in the world.

So, making sure we take in some of our area’s great experiences. And always with an eye on studio.

A big thank you to John for welcoming me into his studio for the day with my camera! Be sure to follow along with John on Instagram to see more of his latest work and glimpses of landscape inspiration.